It’s the resignation heard round the world. Nearly 15 years after taking office, Bob Iger has stepped down as CEO of Disney. A period of unprecedented expansion for the company, the Iger era saw four multibillion-dollar acquisitions, including Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, and, for a cool $71.3 billion, Rupert Murdoch’s Fox fortune. Pile onto that seven blockbusters to hit $1 billion at the global box office in 2019 alone and it’s no wonder people are calling for a good old trust-busting. Too many roads lead to Disney, and not all of them seem paved with gold.

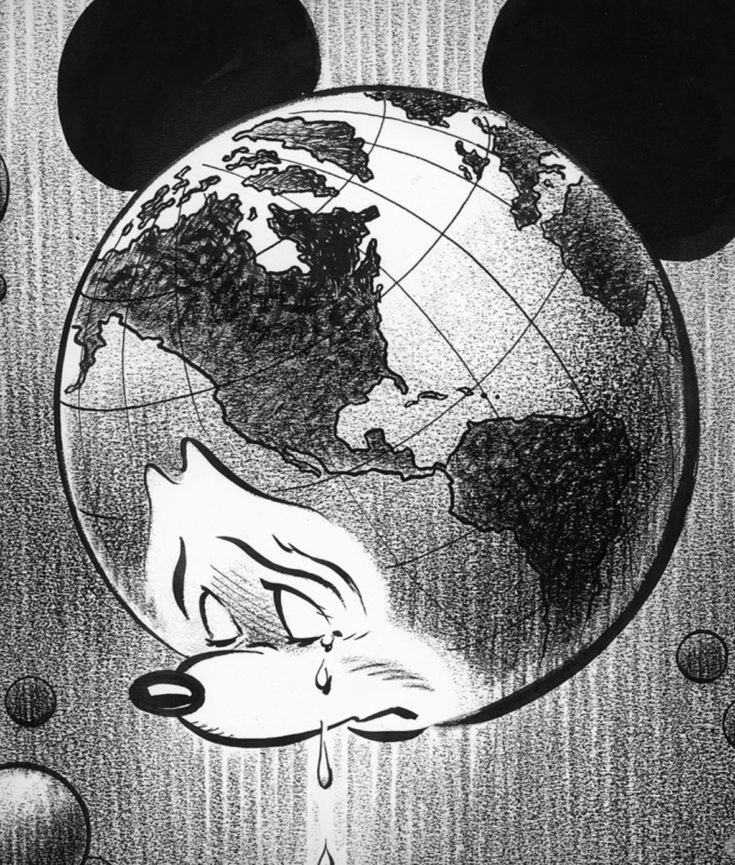

In the age of nostalgia, the Mouse holds a near-monopoly on the best-known franchises which are fast becoming the only event films audiences will pay to see in cinemas. And yet Disney’s PG-13 mandate and executive-level creative control, according to many, poke holes in the integrity of filmmaking. Blaming Disney for the trend toward vanilla cinema is the people’s current soapbox of choice, and the thrust of the anti-Disney argument sounds an awful lot like Dwight Macdonald’s attack on midcentury mass culture, or Masscult. Macdonald was a cultural critic of the snobbish sort, who claimed that popular art, like movies and comic books, is in fact not art at all, but predigested, profit-seeking commercialism. Disney’s investment in big-budget crowd-pleasers has paid off, and Bob Iger is surely a jack of all trades — but is he the kind of Masscult master that Macdonald so openly despised? And should we be afraid for the future of cinematic creativity?

To those of us who have been spoon-fed Disney since birth, it should come as no surprise that Bob Iger stated in an interview with Oprah that Disney is “in the business of manufacturing happiness and entertaining the world.” How we get from this innocuous statement to the popular contention that Disney is an evil empire is a long story, but we can begin telling it with Iger’s own words. There are two key components of his statement with which Dwight Macdonald would have taken issue: “manufacturing” and “the world.” According to Macdonald, art cannot be manufactured. Art is expressed or, at most, crafted. On the contrary, Disney theme parks and cruise lines are manufactured attractions. They are not the kind of outpouring of spirit which marks true art.

This distinction between art and manufactured culture may strike us as somewhat mystical and most definitely outdated, but it crops up constantly in anti-Disney rhetoric. Consider Martin Scorsese’s Marvel takedown. When asked about the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Academy Award-winning director said it was “not cinema,” comparing the superhero films to “theme parks.” The Marvel fandom came for Marty’s well-laureled head, leading him to publish a powerful self-defense in the New York Times. No one puts it better than Scorsese did: “Many films today are perfect products manufactured for immediate consumption … they lack something essential to cinema: the unifying vision of an individual artist.” Who knows what Dwight Macdonald would have thought of Scorsese’s 1970s cinematic milieu, but he surely would have tipped his hat to this well-seasoned defense of the artist’s singular vision.

The importance of the individual artist’s unique subjectivity is not something Disney movies emphasize. How could they? There’s too much money on the line and too many executives eyeing the rough cuts. And when market research dictates what goes in a script, you’d better believe dollars control what falls to the cutting room floor. But the point of this critique is not to say that money is bad for art. It’d be delusional to deny that much art is made in a financial pressure cooker. Rather, it’s Disney’s particular kind of manufacturedness — the workings of a factory designed for brand preservation above all else — that’s worrisome. You can see the stranglehold that the Disney brand has over its own movies: the thematic repetition that has given us franchise fatigue, the uncomfortable transposition of Marvel humor to a Star Wars movie, or the onslaught of live-action remakes that, although poorly reviewed by critics and audiences alike, will keep hitting theaters because they traffic in the ultimate moneymaker — nostalgia. Disney’s films feel so similar to each other not because they are all renditions of the hero’s journey (that’s a pot we’ll never stop dipping into), but because they are all in service of the brand, broadening its reach or cementing its place. Does it have potential as a ride at Disney Shanghai? Greenlight it.

What we’ve seen in the Iger era of Disney is the systematic blurring of the line between advertising and art that Macdonald warned us about half a century ago. “Mass culture is imposed from above,” he wrote. “It is fabricated by technicians hired by business; its audiences are passive consumers, their participation limited to the choice between buying and not buying.” And most people are buying. There’s just not much room at the theater anymore for the capeless crusaders. Bring up the possibility that the Mouse has got the market cornered and, all of a sudden, Disney’s manufacturedness is downright un-American. It’s swallowed entire film studios on its way to stomping out all competition, at least at the box office. The Disney colossus looms large over filmmaking, storytelling, and American identity. Its increased presence abroad is already being viewed as a form of American foreign policy: If Disney agrees to censor an American-made film for a foreign market, is that tantamount to American approval of state censorship?

Setting aside politics, perhaps filmmaking did lose something precious — some personality quirk or Scorsese-esque subjectivity — when Iger stated that Disney is in the business of entertaining “the world.” Or perhaps Disney’s dominion simply proves that it’s a small world after all.

This article originally appeared as an installment of “Movies in Midcult” in The Harvard Crimson on March 9, 2020: https://www.thecrimson.com/column/movies-in-midcult/article/2020/3/9/bob-iger-disney-masscult/